20 Articles, Search Results for '2005/09'

- 2005/09/30 2005.09.30

- 2005/09/28 [워렌 버펫] SPRING MEETING IN OMAHA WITH WARREN BUFFETT

- 2005/09/27 서울, 경인지역 - 라디오 주파수 목록

- 2005/09/25 사랑한다 말해줘!

- 2005/09/19 [워렌 버펫] School of Management (Vanderbilt University) students interviewed..

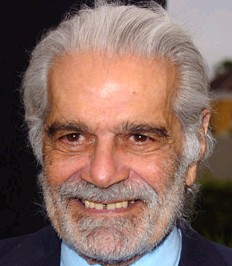

- 2005/09/19 닥터 지바고(Doctor Zhivago)

- 2005/09/19 2005.09.19

- 2005/09/18 2005.09.18

- 2005/09/15 2005.09.15

- 2005/09/14 2005.09.14

- 2005/09/13 2005.09.13

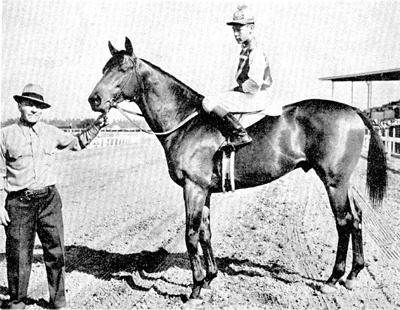

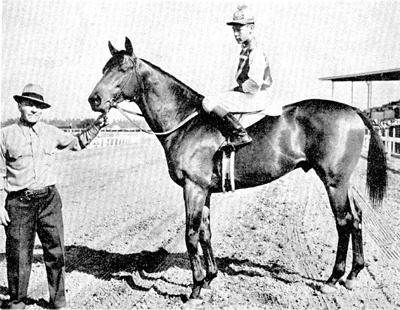

- 2005/09/09 Sunday Silence

- 2005/09/09 Man o' War came close to perfection

- 2005/09/09 Seabiscuit: An American Legend

- 2005/09/09 2005.09.09

- 2005/09/07 2005.09.07

- 2005/09/05 2005.09.05

- 2005/09/04 2005.09.04

- 2005/09/04 2005.09.04

- 2005/09/03 인포 센스

[워렌 버펫] SPRING MEETING IN OMAHA WITH WARREN BUFFETT

2005/09/28 00:24 / Investing/Philosophy & Theory

SPRING MEETING IN OMAHA WITH WARREN BUFFETT

Transcript of "An Evening with Warren Buffett"

October, 2003

Eagle Run Golf Resort

Omaha, Nebraska

Warren Buffett: Last year, as you may remember, was not a good year for Nebraska. It was their worst in about four years. It got so bad that Frank Solich, our coach, was addressing a group like this and he asked for our help and he said, “What we really need is a fullback. And the guy I have in mind would be about 6’4”, and weigh 130 lbs.” He said, “That might seem like kind of an odd requirement for a fullback, but it’s the only kind of guy who could get through the hole if the line opens up.”

So we found our fullback. We have a lot of student athletes at Nebraska and I asked one of them the other day, “What does that big N stand for on your helmet?” And he said, “Knowledge.” He was close.

I’m here to answer your questions. I’ll ask one of them myself. It’s “How did you get involved in the Schwarzenegger campaign?” The answer is, “I won a look-alike contest. Saddam Hussein has a double and Arnold felt he needed one too.”

The Governor mentioned something in his talk that provided me with a question I sometimes get asked by people: “How do I get into a marriage—younger people ask me—how do I make sure I get into a marriage that will last? What do I look for in a spouse?” It’s an important question. They say, should I look for humor, character, intelligence, looks? I tell them, “If you really want a marriage that will last, look for someone with low expectations.” And I’m glad the Governor’s taking that attitude to Washington with him.

Now let’s talk about what’s on your mind. Anything goes. We’re all off the record—although, actually, I see something going on back there (the video camera). I’ll try to be as candid as possible.

Mayor Riordan: Warren, we talk about the gap between the rich and the poor and for a variety of reasons, the number of middle class is dwindling in this country. The buying power of the middle class has been dwindling for the last 30 years. What is this going to lead to? What do you picture the country being like 10 years from now?

I would say that, absent a progressive income tax system, and an estate tax, that the nature of compound interest, and the nature of a more and more specialized economy, will lead to greater and greater differences between the very top and the bottom. If you go back a couple hundred years in this country when we had four million people, you could take people with an IQ of 90, and they could satisfy 80% of the jobs in the country—whether it was farming, or tradespeople or whatever. As the economy has become more specialized, more advanced, and all that, the rewards and the job profile of what pays well compared to other jobs and so on, just gets tilted more and more and more toward people who are wired in some way or have special talents that enable them to prosper in a huge way in a 10 trillion-dollar-plus economy and disparities will widen. And basically we have had a system in this country that, through the tax system in various ways, has sought to temper what a market system will produce in the way of distribution and wealth. You really have unchecked, as it was many years ago, unchecked, you will have families like mine, or whomever, people that bring a small edge over the rest of the populous. They will prosper at a rate that continuously outpaces the others.

And you can see it in entertainment. If you’re a Frank Sinatra or something now and you have some edge over the others—the ability to sing to 280 million people, or if you’re the heavyweight champion with the ability to be seen in the homes of 280 million people or whatever number—it’s worth far more relative to the general laborer pay than it was 50 or 75 years ago. All technology advances and all productivity advances and the pure market system work toward greater inequality of wealth and we have a system in this country where generally we have sought to temper that somewhat through a progressive income tax and through the estate tax in the last ten years or so—and particularly over the last five years—we’ve seen a reversal and I think it could have some very unfortunate consequences over time.

I was lucky to be born here at this time basically. I’m wired to be good at capital allocation. I get no credit for it—I came out of the womb that way. I’ve worked at it, but people work at all kinds of things in this country and all countries to work at the job they’re in. But I was wired in a way where in a huge capitalistic economy, just taking little bites off what’s available, I could amass enormous sums of money. If I’d been born two hundred years ago that would not have been available to me. If I was born in Bangladesh it would not be available to me.

Now people who think they do it all themselves, I pose to them the problem of let’s just assume they were in the womb as one of two identical twins—same DNA, same wiring, everything the same—and a genie came along and said one of you is going to be born in Bangladesh and one of you is going to be born in the United States. All the human qualities are the same. Which one will bid the higher percentage of the income they earn during their life to be the one born in the United States? The bidding would get very spirited. I mean, all these qualities of luck and pluck and all these things that are supposed to take us to the top—you know, like Horatio Alger—would not work as well in Bangladesh as here. This society delivers huge opportunities to people who happen to have the right wiring. And it delivers a pretty damn good result to people who could function here compared to the rest of the world and compared to a hundred years ago; but the disparity will widen absent the taxation system. That’s one of the things you need government for in my view.

Our market system is a wonderful system. You look at this country and it’s interesting. In 1790, we had just a little under four million people. Europe had 100 million people. China had 300 million people. So here’s this little country—and our IQs might be different from the Chinese people or the Europeans—and they have natural resources and we have natural resources, but somehow those four million people have gotten to where they have close to 35% of the GDP of the world, even though they only have 4 billion—4 _ percent of the world’s population. What has happened here? Here we’re in this race—it’s only been going on now for 210 years against 300 million people in someplace else that are just as smart as we are. But somehow our system has delivered this incredible bounty. I believe the two most important things in that and they’re far from perfect—but I think we have more equality of opportunity so that the right people get to the top. The right guy ends up being on the Olympic team of science, or business, or medicine or whatever because we have not had the artificial barriers to quality rising to the top in various areas.

And the second system is the market system and we have had an inducement for people to purchase what people want and that has all kinds of wonderful fallout, but it also results in an incredible inequality of wealth over time and absent the estate taxes—well, with just compound interest, you could take my grandsons and you’d have a significant percentage of wealth eventually. And you need something that tempers where the market system leads to but you don’t want to screw up the market system. You want to let them make it first. You want to keep the Andy Groves or whether it’s Michael Dell or whomever, you want to keep those people working, long after they’ve got all the things they need in life. You want that energy and that talent working, because it does work for the benefit of everybody, but then you need to have something that prevents huge concentrations of wealth.

QUESTION: Along the same lines, I heard a speaker from India who talked of why America’s thriving—because in India, you know your dad’s a chemical engineer and that’s what you’re gonna be—whereas Americans under Christianity and capitalism think we can take and should get whatever we want. My question is how would you solve the terrorism threat—when people hate us now because of our wealth and freedom?

It’s the ultimate problem. I felt that way after 1945 because essentially you always have people who are psychotic or megalomaniacs or just plain evil or religious fanatics or whatever it may be. There is a certain percentage of people who for one reason or another are sociopaths and thousands of years ago their ability to afflict harm on their fellow man was the ability to throw a rock at somebody and it gradually went to bows and arrows and guns and a few things. But up until 1945 the ability of misdirected people—which will be more or less proportionate to the population over time (maybe you could make an argument that prosperity may reduce it a little bit) but there’s just a lot of screwy people. I mean, I’ve been to the mental institutions in Nebraska and my father-in-law taught psychology and I used to go down with him—I mean, there are just people who are not very well fit for society and until 1945 their ability to afflict harm on their fellow man had progressed, but it had progressed at a tolerable level. At the time of Hiroshima and from that point forward, there’s been this exponential increase in the ability of deranged people who one way or the other—perhaps leading governments, perhaps acting some other way—to inflict incredible harm on their fellow man.

It takes four things. It takes intent and there will always be a certain amount of intent in the world. There will be people that are envious; there will be people that are crazy and so on.

It takes intent. It takes knowledge. It takes materials. It takes deliverability. The knowledge has spread. We had a monopoly on nuclear knowledge in 1945 and thank God we had it because if Hitler hadn’t been so anti-Semitic, basically, he might well have had it before we had it. But we got the knowledge first. Most of you aren’t old enough to remember, but Hitler was lobbing those B-1s and B-2s over into London, but the warheads were nothing. But if he’d gotten them first, it would be a different world, or maybe no world.

So the knowledge since ’45, when we had the monopoly on this incredible knowledge, has spread. You have Pakistan, you have India, you have individual groups. Materials are tougher in the nuclear arena. Now if you get into bio the materials get easier but we still have the same levels of damage. But you get suicide bombers and things like that and the materials are peanuts in terms of cost and the knowledge is there. It is a problem that we do not have a perfect answer for and all we can try to do is reduce the probabilities of somebody successfully doing something on a large scale. It will happen. It will happen with nuclear. In my view it will happen with bio. Probably a little more likely to happen with bio in the next, say, ten years than with nuclear but the truth is there are a lot of people that have the ability to do things. I’m in the insurance business, and anything that can happen will happen.

If you take the last 300 years in America, where do you think the largest earthquake was in the continental United States? It was in New Madrid, Missouri. 8.6. The Mississippi River ran backwards. Church bells rang in Boston. Another big one was in Columbia, South Carolina, and everybody’s forgotten about that. It killed 70 or 80 people, 6. something. Things happen over time. You just can’t keep drawing balls out of a barrel with ten thousand white balls and four black balls, we’ll say, without eventually drawing a black ball. We almost drew one during the Cuban missile crisis. It was touch and go. We sent the second message, then the contact with the guy from ABC. But there was a lot of luck involved. I know people who were there at the table. And they didn’t know if their kids were going to be alive some weeks later. But we got through it. And basically, we’ve been very lucky, but we’ve also done the right things over that time. It doesn’t work forever. The bio thing, I mean, it’s scary. Anthrax isn’t as easy to deliver. The deliverability of Anthrax is a problem. You can take the amounts in those few envelopes and it would kill a hundred thousand people but it’s a problem to disperse. The progress of weaponry over the years (if you want to call it progress) has been dramatic.

When I formed my foundation in the late ‘60s, I said that the number one problem was the nuclear threat and I just don’t know how to attack it with money very well. I support something called the nuclear threat initiative.

The great problems of society are the ones money won’t solve. Probably true in your families too. The problems you have where money doesn’t help—those are the real problems. The problems that money can help, this country can one way or another solve. And the ultimate one is the one you mentioned there. There are people in the world that want to do us great harm. We’re more the target than anybody else. Some of them will have the knowledge, fewer will have the materials; they won’t have the deliverability.

But North Korea—there’s a small probability in the next year that something happens with North Korea. I don’t know whether it’s .01 or .03 or .005, but it is a probability. There’s some probability of it. And there’s a probability of all kinds of other things. People would have thought it was science fiction if you’d have written about what would happen at the World Trade Center a few years ago. That 20-odd people could carry it off with box cutters and so on. It’s the problem of mankind. Our job is to reduce the probability in every way we can. The number one way is to try and do whatever you can to deter the further spread of nuclear weapons. Like India and Pakistan each have that ability and they have the hatred that’s existed over the years and the sort of incidents that developed by accident.

President Clinton was here last Saturday at my daughter’s house and we had lunch and we were talking about India and Pakistan. He worked on a solution I think it was right on the eve of the State of the Union message a few years back. And he didn’t know whether something was going to break out or not. The consequences are just huge. It’s the number one problem of mankind. I don’t have any great answers, but I think that the Commander in Chief—it’s his number one job. Whatever it may take in terms of our borders, in terms of solving the problems of stockpiles around the country, cooperating with the Russians, get rid of a lot of the material like that. It will be the problem of your lifetime and your children’s and your grandchildren’s.

With all the storm of regulation in the last couple of years on the subject of corporate governance, could you say something about your views of the essentials of good corporate governance?

Well, I’ve got a somewhat different view. I’ve been on 19 public boards and corporate business boards over 40+ years, public companies, not counting anything Berkshire controls. And I’ve seen a lot of interaction of boards. And the problem has been overwhelmingly that boards, despite the fact that they exist in a business environment, tend to be social organizations. I think it’s very difficult for these people on the board—(I was put on the board of Coca-Cola in 1988)—to go in there and start questioning Roberto Goizueta in terms of his compensation. And incidentally we didn’t even know as board members what the compensation was. I mean you read the proxy statement unless you were on the comp committee. And they never put me on the comp committee. And I’ve been on all kinds of committees. They’ll put me on the greetings committee, the gardening committee—anything really, the dance committee. They don’t put me on the comp committee—I wonder why?

But it’s a social organization to a great degree. And generally speaking, the only thing, absent a very large shareholder who’s unhappy with something going on—the only things that really cause change is when people on the board get embarrassed. Because you get a bunch of big shots on the board. I call it “elephant-bumping” when you go to board meetings. Everybody looks around and you see all these elephants, and you think “I must be an elephant too.” It’s very reassuring. You don’t want to sit there and belch in a board meeting because it just isn’t done, like questioning comps and questioning acquisitions, and other things worse than belching (we won’t get into what that is). But it’s a social operation and the question is—how do you break out of something like that? And it’s not easy. The hardest problem is dealing with mediocrity.

I mean, if Frank Solich at Nebraska has a mediocre quarterback or whatever, he’s gotta do something about it or he won’t be coaching next year. When a Fortune 500 company has a mediocre CEO—a perfectly decent guy, good family man, a friend of yours or picked you for the board, what’s your incentive to, perhaps, you know, to get rid of him? It isn’t going to happen. It just doesn’t make that much difference. And of course when you get to the comp committee, it’s ridiculous, because you have a CEO on one side to whom this whole thing is terribly important and then you have a comp committee for whom it’s play money. I mean that’s what I call it—play money—because it doesn’t mean anything to him.

So you have an inequality of marketing intensity that’s very difficult to write rules to solve, frankly. But I think the ideal quarterback (and we talk about this when we talk about the annual report), but you want somebody that’s business-savvy. There are a lot of people on boards that are very smart people but they don’t know anything about business. And if I was on a hospital board, I wouldn’t know a thing about running a hospital or medicine. And I wouldn’t after a year or two if a bunch of guys came in in white coats every meeting and explained something to me for an hour or with a power point demo—I wouldn’t know anything about it. I just wouldn’t understand it. I could be sold any bill of goods they wanted to sell me.

And the same would be true if I was at Cal Tech and they were talking physics. And it’s not that I’m not smart enough to do crossword puzzles or something. But I just don’t know the game. And there are loads of those people on corporate boards in America that have big names and they have no idea how to run a lemonade stand. And it’s nothing wrong with them—they know how to do very well what they do. So you need business savvy, you need a shareholder orientation, which is lacking in a great many directors. You need interest, they’ve gotta want to show up because they’re actually interested in the business, and not because they’re interested in the fee or something.

And then you do need something called independence. But independence has statutory defined just does not work for them. We at Berkshire have a whole bunch of people who would meet every statutory test of independence, but if we paid them a lot of money (which we don’t at Berkshire for reasons I’ll get into—it may be obvious if you know me). But if we paid them $75,000 a year and their total income’s $200,000, we’ll say, and they’re hoping to get on one more board and get another 75—they are not independent. But real independence comes from an independence of mind and partly, at Berkshire we pay our directors basically nothing. We don’t buy directors and officers insurance. They’re not taking home insurance. We’re just about the only ones on the New York Stock Exchange who don’t buy it. We want directors who have a lot of their own money in the stock. Not options. Not stock grants. Their own money. Just like I do and just like a lot of other people—and like our owners do. We want them to have no interest in the fees they’re getting so we don’t pay them anything. We want them on the hook for bad decisions. If they’ve got the wrong guy running it we want them to suffer just like the shareholders do. So we leave them with a downside. And we’ve got some very business-savvy people. They know business and in each case they’ve got at least a million dollars in stock and they get $900 a year. So their interests are aligned with the shareholders. And I could have ten people who met the stock exchange definition. They’d all have prominent names. And if the money was important to them they’re not independent. They’re not any more independent than the salaried employee of Berkshire if they’re getting a third or a fourth of their income from it.

So it’s a difficult question to tackle. There are two functions, really, that a board has to look at—you want to have the right CEO and you want to make sure he or she doesn’t overreach. And if you get that job done, that’s all you need. You need the right players at bat and then you’ve got to make sure they’re not taking advantage of the people who are on the team, basically. And the right CEO question is very tough, if you’re on the board and you’ve got a reasonably good person, but you know you could go out and get better.

And the overreaching has been very tough in recent years. Frankly people want to appraise something. They’ve brought in consultants and the consultants were basically hired by the management. And if they weren’t they still do what the management wants so they’ll get recommended to other firms. And it’s been a one-sided, dice is loaded game. And I know what our approach has been at Berkshire in order to tackle that. And it’s been quite unorthodox. But we’ll do it. We still have to follow the rules. I have to make sure we qualify in other ways too. But I don’t pay any attention except to make sure we follow the law. But that is not the way we select directors. And interestingly enough, I said in the annual report we have to get some more. And I heard from about 30 people and I said they had to have owned their stock for some time. And these people had millions of dollars, each one of them, and they were willing to take the job. And they were interested in the business. And we picked a couple and we may pick another one or two.

I think some companies are making some progress. I think Jeff Immelt, for example, at GE is leading the way to some degree in terms of trying to set up the company’s governance in a way that makes the most sense to the shareholders of General Electric. And he’s taken the lead in that. He wants to do the right thing and he’s going to be around there for 15 or 20 years and it’s interesting to me—that kind of person. And you’ll find that. But basically, most CEOs have learned how the game assists them and they’re not going to give it up willingly.

Is there anybody I’ve forgotten to offend?

QUESTION: I’m interested in your opinion of American manufacturing. I know that you’ve invested in Montgomery and mobile homes and Shaw Industries and I know that most of those companies don’t have the breadth of Chinese manufacturing coming at them. And I was wondering if that is an absolute staple of how you analyze a manufacturing company; is it childproof?

Berkshire Hathaway started the textile business; in fact it goes back into the 1800s if you go to all the predecessor companies. I got in in 1964. We had a couple thousand employees in New Bedford; it was down from 12,000 by the time I got there. Twelve thousand had cut down to two thousand. We had a couple thousand people—very decent workers, working for low wages. It was a lousy job in terms of pay. They were skilled at what they did. Mostly Portuguese. New Bedford was a whaling town and there wasn’t one thing wrong with that labor force. And we got killed, basically. If you talk about comparative advantage in this world, people are willing to work a lot cheaper someplace else. And there wasn’t any answer. And when you talk about retraining people—these were people 55 years of age. I mean, a prosperous society has to provide a safety net for people like that. Through no fault of their own, they were in a position of being a horse when the tractor came in. There’s no other way to put it. They didn’t have the ability, at 55 or 60, to find work as computer experts. The free market did them in. The free market, of course, does all kinds of good things in this country, but you have to take care of people like that. That happened in textiles; it’s still happening in textiles. It’s wiping out the Burlington industry, WestPoint companies, Tultex. Bankruptcy after bankruptcy after bankruptcy. They won’t come back.

I also got into shoes. This country literally—Americans buy 1.2 billion pairs of shoes a year. We’re a nation of Imelda Marcos’s. I buy a pair of shoes about every ten years or so. But a billion 200,000 pairs a year. Practically all of that was made in this country except the very high-price lines, 40 years ago, you know Rockford, Massachusetts. It’s down probably under 4% now. We were one of the last American manufacturers of American shoes. We did them up in Dexter, Maine. I bought the company some years ago and they had terrific styling and the whole works. We had a great labor force. Management loved the people, the people loved the management and we were making decent money and the money just went down the tubes. Because somebody else was willing to work for one-tenth of the wages of the people of Dexter, Maine. There is no domestic shoe industry as a practical matter today.

The same thing is now happening in furniture as Bill Child will tell you. Bill, twenty years ago, I don’t know what percentage of your purchases were made over there. But they went to North Carolina, they went to Drexel, to Broyhill and all these people. And now we go there and a lot of those people are buying over in China, so we go directly and buy it ourselves. We’re big enough so we can make our own direct purchases instead of somebody else buying it and stamping their name on it and marking it up 20%. The furniture industry, at least in anything but high labor content, is leaving us and it’s not the fault of the workers at all. It’s just the nature of the globalized sourcing, in effect.

Now you mention Shaw Industries. Shaw is the largest manufacturer of carpet in the world. We have sales of 14.5 billion now. Labor’s only 15% of carpet. As a practical matter, if you analyze all the cost factors and everything, it will go there. We also own Fruit of the Loom. That manufacturing, 80% of it has gone to Central America. First it went to Mexico and now it actually goes to Guatamala and places like that. As long as we believe in free trade in this country, you’re going to have all those high labor content businesses—actually even things like software, now India has become a real factor in that industry. And Bill Gates with Microsoft is working more and more with people in India. It’s a real problem in this country. I don’t know what industries are next. But you’re talking millions of people when you go from textiles, and shoes, and now furniture, and there aren’t great replacement jobs for those people. They’re not going to move into all kinds of wonderful jobs.

There’s a significant percentage of your population that is non-productive so that productive people have to turn around and be offered more. It puts more and more strains in the economy. The fact is, we’re seeing some of that.

I’ve learned the hard way. I’ve learned in the shoe business and the textile business. And I’ve learned the hard way. There are times you cannot fight. You cannot fight with labor at X here and at one-tenth, or even a fifth, or fourth X someplace else. People aren’t going to buy it from you just because it says “Made in America” on it. They’ll go to Wal-Mart and if our Fruit of the Loom underwear—forget the quality—if it has the best price on it, we’re gonna sell it. If somebody figures out how to do it for 50 cents-a-three-pack or something cheaper, then we’ve got a problem. We’re okay because we’ve got 16,000 people working for us outside the United States and about 4,000 people working for us in the United States.

QUESTION: I’ve listened to you for a long time and studied your work. It seems to have evolved as you’ve gotten into things like NetJets and recently I’ve read about your investments in China and the oil industry. And I just wanted you to give us some insight with your desire to not be capital-intensive—industries that require any capital spending—how NetJet works.

Well, we try and get, you know, flight. That’s sort of funny. Flight is a very expensive piece of equipment. The airline business, it’s been the great capital trap of all time. If you look at the history of the airline business, it’s been about a hundred years exactly. No money has been made transporting people. I mean, just imagine, you go back to Kitty Hawk in 1903 or whenever it was, and you have this picture all of a sudden of what it’s going to look like with planes carrying four hundred people, going coast to coast in five hours and all of the things that would open up. And you say, you know this is unbelievable. Everybody’s going to get rich. And yet, it’s been a loss, in spite of all the capital that’s been put in.

If there’d been a capitalist down in Kitty Hawk he should have shot down all of them. There’d be a statue of him in my office. Here’s the man that shot down Orville and saved us all a fortune. But the reason it’s a lousy business is because the equipment is so expensive and also because of the costs. And because it’s a commodity business to a big extent. I mean, in the end, if you’re running XYZ Airline and you open up USA Today in the morning and your competitor’s advertising a lower price, you’ve gotta match it that day.

That’s not true if you sell See’s candy, like we do in the West, or something of the sort. You just tell people that cheap candy’ll kill you. If you’re in the commodity business, with huge capital requirements, heavily unionized, it’s just going to be a capital trap. And that’s been the case. In our case, at NetJets, the customer owns part of the plane, but they save a lot of money as compared to owning a whole plane. You know, the more you buy, the more you save, or some crazy thing like that. But I’ve met a few customers here and nobody gives it up. I mean, my daughter here is a user of it—she’d trade her parents away for another fifty dollars of NetJets probably. Once you’ve been with NetJets going back to commercial aviation is like going back to holding hands. That’s not the direction you want to go.

PetroChina you mentioned which is a huge oil company, that’s very capital-intensive—we just own stock in that. That’s like our stock in Coca-Cola. It’s true; it’s the only stock we’ve owned in China. But there are company stocks you can own in China that are big companies. PetroChina’s a very big company. PetroChina, turns out, produces almost as much oil, 80% as much as much as Exxon-Mobile, we’re talking real numbers there. But it’s also very capital intensive. But compared to the Exxon-Mobiles of the world, Chevron and those, it’s selling at a very low price. And it should sell for a lower price. Although one of the reporters at our annual meeting, afterwards he said, how can you buy stock in a company run by a bunch of Communists? And I said after seeing some of American management I actually preferred that. It’s just a stock with us.

QUESTION: We’re all going to grow older. Who should administer, I mean, how are we going to handle our medical economy situation?

There’s a good book that just came out by the guy that runs Kaiser. I’m trying to think of the name of it. It describes the problems that we are in already and that we face. Like 13 or 14% of GDP is going to turn into higher percentages. And that is an incredible percentage. It’s almost twice what anybody in the world pays. And the answer in medicine with all the developments that go on, and with the fact that treatment basically gets more and more expensive and people live longer and longer, one way or another it has to be rationed. That’s a terrible word to use in connection with something like medicine. But it’s happened. It happens over the years, it may be rationed by waiting time, in some socialist systems. It may be rationed by money when you get to very high specificities. But in the end, it’s unlimited demand, virtually, and in terms of the costs, in terms of certain illnesses. And this country I don’t think will work very well if 20% of GDP is going to medicine. Most medicine, obviously, involves people beyond productive age.

Young people don’t support you. Old people don’t support you. It costs $11,000 per student in the New York City public school system. Per family of four, it’s $44,000 a year. Somebody’s paying for it. That’s a tax on people who produce. It’s a tax we bear, kind of an intergenerational compact we have over the years that you take care of me, then I produce in the middle, then you take care of me when I get old. Society does it, society should do it. But that equation gets tougher and tougher as you get more and more people in the young part and the older part because the people between 21 and 65 are the people who have to turn on the output to take care of everybody; and that means not only the manufacturing businesses but in services like medicine.

We’re now starting to hit that again. We had a honeymoon period for a few years, where in effect, hospital stays were reduced. It used to be in terms of maternity wards, people would be in for a baby and might be in for a number of days, and we’re cutting it down. HMOs came in and bargained down prices and all that sort of thing for awhile. But now we’re out of that phase and you’re starting to see these 10% a year increases. And you start getting 10% a year increases for companies in a world where the GDP is drawing 3-4% a year. And somewhere it starts biting and biting badly. So we will see. We will see some systems that put in more perks as they go along. There’s just no question about it.

QUESTION: I wanted to go back and ask a question. When you buy a company, is it a selection process, or a voter-type process?

It’s selection that pulls the culture. And the culture evolves more or less. But selection you start with. The first thing I look at when somebody wants to sell me a business before making a decision—do they love the money or do they love the company? If somebody loves painting, they may make a lot of money selling paintings, but they’re going to keep painting. If they love playing golf, they may make a ton of money, but they’ll keep playing golf. Jack Nicklaus will be out on the Senior Tour, whatever. If they love the money, they’re going to take the money, and they’ll promise me they’ll go to work for awhile; then after six months, they or their spouse will say, “Why are you jumping out of bed at 7 in the morning? You spent 40 years building this business and now you have all the money in the world and you’re still doing the same thing as before just so you can send a lot of money to Omaha.”

I think that decision is the most important question I’ve got to ask. I ask questions about the economic characteristics of the business and the price I’m paying, but I don’t have any management in Omaha. We’ve got 16 people in Omaha and we’ve got 165,000 employees. So we just don’t have anybody to send out. We don’t have any firemen. So I have to count on the people who sell me the business, they take hundreds of millions of dollars, like Rich Santulli at NetJets and they’re still going to want to get up at 5:30 in the morning and Thanksgiving weekend when everyone’s in such hurry because they all want planes at the same time. Solving those problems and the thunder storms in the east and whatever it may be. And when they get all through at the end of the day, wanna do it again the next day.

We’ve had a problem frankly, in finding those kinds of people, because three-quarters of our managers, at least, have more money than they or their kids or their grandchildren will ever need. They’ve monetized a lifetime of work or maybe their parents’ work or their grandparents’ work. But they’ve monetized that when they handed the business to us. And now they’ve got an option. And if they love the business, they can’t stop. Why do I work? I can’t tell you how much I love what I do. I would pay a lot of money (of course we don’t want the shareholders to know)—but I would pay a lot of money to have this job. I mean, I would do it under any circumstances. But the truth is I could anything in the world that I want, but this is what I like doing. It has nothing to do with how much I get paid. It just has to do with two things. It has to do with me getting to do what I like to do the way I want to do it. If somebody was telling me what I had to do every day I’d be gone tomorrow. Why in the world would I want to do that with the kind of money I have if I was being told what I had to do and how I had to do it, and whether to part my hair on the right or the left, or what to wear to the office or anything like that. I’d just say goodbye.

And secondly, I like appreciation. I like the fact that by and large our shareholders are appreciative. I’ve got an audience that I like and that’s what causes me to work when I don’t need the money. It’s probably what will cause other people to work in the businesses that we buy, assuming they love the business to start with. So we let them run their own business to an extraordinary degree. And we applaud. And if they get applause from me they’re getting it from a knowledgeable audience. I mean, I know business and I know enough about business to know when applause is due and when it isn’t. So they’re getting it from a good critic, as far as they’re concerned. And they’re getting it from our shareholders in turn, because I pass along the reasons for applause. And that’s what causes people to love it. They’ve got to love what they do. There’s just no way around it. And if they don’t, money isn’t going to keep them.

And we’ve never had, well, since 1965 I don’t know how many businesses we’ve acquired, but dozens and dozens. And we have never had a CEO leave us for another job voluntarily. We’ve had to make a couple of changes in 35 years, except this year in one company where the founder brought in a CEO to work jointly with her and the two of them, it just didn’t work. And that was over in a couple of months. But both of them feel good about Berkshire and it just doesn’t work to have two people try to run that kind of business. And it usually doesn’t work, but sometimes it works very well. We’ve had cases where it does work very well. So there’s no magic to it, but you’d better be sure that they love the business in the first place and that you let them paint their own painting. I mean, I feel like I’m on my back, and there’s the Sistine Chapel, and I’m painting away; it’s my painting, and somebody says, “Why don’t you use more red instead of blue?” Goodbye. It’s my painting. And I don’t care what they sell it for. That’s not part of it. The painting itself will never be finished. That’s one of the great things about it.

And I like it when people say, “Gee, that’s a pretty good-looking painting.” To me, that’s what management is about. Management is getting things done through other people that you want to get done. The way you get it done through other people—is to get talented people and let them work in a way that causes them to be more excited about it than they’ve ever been before. And we get that. Flight Safety. Al Ueltschi started that in 1951 with $10,000. Here’s a guy that flew Lindbergh. He’s 85 years old now. He built his own business and he got a billion dollars worth of Berkshire stock as a matter of record. Here’s what else he does—he works seven days a week and he solved his problem when he sold the business to Berkshire some years ago. Because here he built this thing—it was his painting—and he worried about what’s going to happen when I die? I have a very simple rule. I say, look, you can sell this painting today and we’ll hang it in the Metropolitan Museum or you can sell it to some LPO operator and it will hang in a board room.

Now if you want this painting you’ve spent your whole life on hanging in a board room, that’s fair enough. And maybe a few bucks is worth it. But we’ll put it in the Metropolitan Museum and we’ll name a special wing after it; and not only that, you go on and keep painting. And that’s what Al wants. And when he sold it to me, his life is better afterwards, because that’s the one thing he worries about. You worry about your children. It was too important, when he’d built this thing for 40 or 50 years. A line I used with him—I told him, look, don’t worry about it. If you die tomorrow, some 26-year-old trust officer is likely to auction the place off. And that drives him crazy. But you do want to know what happens to your family. You do want to know what happens to your business. And that filters out all kinds of other things. I mean, in the end we’ve never bought a business at an auction. It won’t happen. We’re not interested in that. They dress up the figures and do all these other things. It’s not going to happen. But we’ve got a filter so I don’t have to review a thousand to buy two or something like that. I’m probably looking at three to buy two or something of the sort because we have filters they pass through before we even think about it. And we make deals over the phone. We bought the McLain Company from Wal-Mart—22 billion in sales—but to complete the deal was 29 days. The CFO from Wal-Mart came up to Omaha. We talked for a couple of hours and we shook hands on a price. He called down there, came back and said okay. And he said, what due diligence do I realize? And I said, “I’ve just done my due diligence. I’ve asked you a few questions.” We closed it 29 days later. We’ve never had a deal that closed that fast before the one with Wal-Mart. They loved it and we loved it. We’ve got a great guy running it.

That’s what I want to do in life. I mean, I don’t want to go through buying things at auction and trying to find the MBAs that are coming out from other places. I’d rather just find four hundred diggers that want to keep playing the game.

QUESTION: What’s the best business you’ve ever invested in and is there a favorite deal you’ve ever done?

My favorite deal’s going to be the next deal. It’s tomorrow morning—it’s going to be more fun than any day I’ve had a job as far as I’m concerned. And that’s the way it is in what I do. We were talking about it at dinner, I mean the best kind of business to be in is something where you sell something that costs a penny and sells for a dollar and is habit forming. We haven’t found that yet but we sell things a little like that. We sell candy in the West, See’s Candy. Now unfortunately boxed chocolates are not big in this country, there’s about 1 pound per capita. Everybody loves to eat them and get them as gifts but they don’t buy them to eat themselves, it’s a very interesting phenomenon. I mean there’s nobody here that wouldn’t like to get a box of chocolates for Christmas or when they are in the hospital or a birthday. But you don’t go to a shop and buy it whereas in other parts of the world people do that, so it’s a small business but it’s still an important business. It’s a great gift and very seasonal. I mean, we made 55 million dollars last year. We made 50 million in the three weeks before Christmas.

Our company saw what is apparently a come to Jesus moment. Can you imagine going home on Valentine’s Day, you know and saying, there’s my sweetheart and unwrap this box saying Happy Valentine’s, Dear, I took the low bid. Price is not a determining factor. If you are selling something for five dollars a pound, you don’t have to worry about somebody selling for $4.95 a pound and taking away the market like you do in a lot of things. It’s what’s in the mind that counts. And if you gave a box of chocolates on your first date to some girl and she kissed you, we all knew. As long as they are our chocolates. If she slapped your face, we’re never going to get you back, that’s not going to work. It’s got to be very good chocolate obviously, but everybody in California has something in their mind about See’s Chocolates. Just like everybody in the world virtually has something in their mind about Coca-Cola. They have something that I call “share of mind” and “share of market.” They’ve got something in their mind. Now they aren’t going to have 28 things in their mind. All we want with Coca-Cola are those that are associated with happiness. So we want it at Disney World, we want it at Disneyland, we want it at a baseball game. We want it everyplace people are happy. We want Coca-Cola because we want that association. Tastes terrific to drink too.

But it’s going to be something in the mind about it that makes people feel good about the product. So someone else is selling something in a can for one penny less—they don’t shift. And if you say RC Cola to people, it’s been around for 75 years, but there’s something in your mind about RC Cola. Other than that, it doesn’t bring anything to mind and if you are selling a consumer product you want it to be in as many minds as possible with as favorable connotations as possible. And the truth is you can go in, this is one of the ways I look at business, I can give you a billion dollars and tell you to go to California and try and beat us in the boxed chocolate business and you’d say to yourself, how am I going to do it? Am I going to sell them for cheaper prices? Am I going to get new outputs? You can’t displace it because you can’t change what’s in peoples’ minds with a billion dollar advertising campaign or anything of the sort.

You could build a shoe factory in China that will put us out of business because in the end you may care a little bit. Remember Florhseim shoes or Big Men shoes 20 years ago, they’re gone. You don’t really care what shoe, you care what it looks like and if it’s a name you recognize, fine. You don’t pay something extra for it and you sure as hell don’t look at the bottom of the sole and see if it says “Made in the USA” or not. You really need to be in something where cost is not the controlling factor. Hershey bars—you know, you go into a drug store and say, “I want a Hershey bar,” and the guy says, “I’ve got this private label I make myself, same size as a Hershey bar and it’s a nickel cheaper.” You walk across the street and buy a Hershey bar some place else. That’s when you have a business. It’s when you walk across the street if the guy tries to sell you something, even if it is a little cheaper.

But if you sell wheat, my son lost a farm and it’s a terrible business, and I told him the day someone walks into a place like this and says, “I’d like some of [name-brand] corn, please,” you know you are in a good business. But when they just say “Bring me some corn,” it’s a lousy business. In fact, such a lousy business, they had a fella that I read about that he won the lottery and he was a farmer here in Nebraska that won 20 million dollars and the TV crew went out to him and asked him, “What are you going to do with the 20 million dollars?” He says, “I think I’ll just keep farming ‘til it’s all gone.” That’s what happens when you are in the commodity business. You don’t want to go near it.

QUESTION: What do you think about the prospect of the current economy and how would you change economic policy?

I pay no attention to economic forecasting. Your children are, absent of the terrorism thing, but in terms of material wealth per capita, your kids are going to live better than you and your grandchildren will live better. And again in the 20th century, real GDP per capita, real GDP, one of seven for one in this country, just think of that, seven times. You can cash that out to fewer hours of work or more product or all kinds of things. But it’s a wonderful, wonderful economy and it’ll get better over time. Now to make any given 20 or 30, assuming I have 20 years left, there will be a few lousy years and there will be a few so-so years and most will be pretty good years and a couple fabulous years and I don’t know in what order they are going to come. But if I’m a good golfer and I haven’t played a course here before and I knew there would be some par 5s and some par 3s, I’m going to take some more strokes on the par 5s than on the par 3s on average. The importance is that I play, that I play each hole well. In the end I will end up with a good score. I can’t just go around and play the par 3s. I can’t do that in business. I worry about being in good businesses with good people. That’s all I focus on. Never base a decision in business, I’ve never based a decision on expansion of a business or anything like that based on an economic forecast because A) it’s not reliable and B) it’s not important. What is important is where we are going to be in 5 or 10 or 20 years in the country and will we be better off for this. So we don’t have any clear-cut economic forecasters. My partner Charlie and I never talk about it. We just talk about how can we put the money out in businesses that we have owned forever, with the kind of people we can trust.

QUESTION: Could you talk a little about your foray into telecom and maybe about the MCI convergence?

There hasn’t been much of a foray in telecom to start with that. Telecom is not a business I understand very well. I have no insights into that business. It’s always struck me as a very competitive commodity-type business, capital intensive. It’s just not a game where I have any kind of any interest at all. I’d rather sell candy or something of the sort, where you can understand the competitive advantage. But I don’t like businesses that are going to change a lot. I like Gillette, you know a hundred years ago almost, they were the dumb regular blade. Like value, they sell over 70 percent of the blades to the rest of the world, in the world—70 percent. Everybody knows how to make them; they don’t have to steal the technology; they don’t have to distribute them. But here’s a company that has 70 percent overtime. So it’s a great, great business. It will dominate 10 years from now. Dominate 20 years from now. Berkley will dominate surely 10 years from now or 20 years from now. Coca-Cola will dominate, but who’s going to do what in telecom? I don’t even know what’s happened in the past very well and I have no idea in a fast-folding industry what’s going to happen. So I view the change as beneficial to society but potentially very harmful to investors. Absence of change is how you get rich in investing. If you buy something that’s very good and you don’t worry about it changing on you and there’s certain mysteries that run themselves with that, there’s certain industries that don’t. Anything with a lot of technology is something to be very wrong on in a short period of time. Now people say you can be very right on it too but I don’t know enough to know the difference. I haven’t run into very many people that do, occasionally people think they do but it’s very hard to predict.

Look at the television industry. Television changes the lives of all of us in this room. I don’t think there’s a television set being manufactured in the United States that there aren’t 20 million of them being sold that were manufactured elsewhere. Radio came along and nobody made money after a little while making radio sets. There’s just all kinds of things that are beneficial for society that involve change. Just take the computer business. If you look at the people that got into computers 30 years ago, you had people like, well I can go down the list, it was a lousy business. Wonderful for society, grew up on it. But it was like, we might use the example of the auto business. 2,000 auto companies in the United States were formed 2,000. There was an Omaha Motor Company. There was a Nebraska Motor Company. There was Maytag, there was Dupont. What you’ve got left, you’ve got two companies struggling and the third sold out to the Germans. They are running the company basically for the pensioners now. It’s been a terrible business model for this country. But it’s thoroughly fascinating. It’s little niche businesses like WD-40, or something like that, that do very well. Just a little something to stick together. Auto manufacturers turn out millions of cars and hundreds of thousands of people work there and they are lousy businesses. Capitalism has had growth in that sense. You can develop a good restaurant and somebody can come along and copy it the next day and figure out something new to add to the menu or add a little more parking. People are always looking at successful models and going after them. That’s terrific for the consumer. It can be very brutal to be in those kinds of businesses. Like McDonalds sort of owned the world 20 years ago, but not now. Wendy’s is doing better. Burger King is kind of struggling. It’s tough. I don’t like tough.

QUESTION: Tell us a little bit about why you’re involved in California.

California: A) I’ve spent more time in California than any other state, except for Nebraska. I’ve had a home up there for 30 years. The big reason is California is too big to ignore. California is the size of France in terms of GDP. I mean it is twelve or thirteen percent, or whatever of the United States’ economy and it’s important to Nebraska that California do well. We will not do wonderfully in Nebraska if California is a mess. And California is a fiscal mess. I mean, in May of this year we were approached by investment bankers presenting the state of California because California needed to sell 11 billion warrants. These were warrants that were going to be issued in June, due next June to tide over the deficit. California couldn’t sell those. The only way California could sell 11 billion was to get someone like Berkshire Hathaway or somebody else to guarantee, if worse came to worse, we would buy those bonds at junk bond prices. In other words, if they couldn’t find any buyer in the world to buy them we would stand by it. We offered to do it for a price.

A group of seven banks led by Merrill Lynch, and Citicorp, got paid 84 million dollars. They got paid three quarters of 1 percent for doing nothing but guaranteeing that if California could not find any buyer in the world between now and next June they would step up and buy this 11 billion. That got them past the June crisis. Their credit card wasn’t any good without a guarantor. What happens in the state of California affects the state of the country, and that was the situation. Now they face 3 billion revenue anticipation notes. They are talking about paying 1 percent to get a letter of credit backing those, these are due next June. From now to next June on the market and they are going to need to pay 100 basis points for just the guarantee that somehow somebody will buy these damn things, cause if they don’t they’ve got a couple other things in the works.

California, in my view, has until next June when this batch with come due plus they will be facing further deficits. They have until next June to be credible in the world on their own in terms of the financial markets. Because the financial markets don’t have to buy California paper, I mean there’s nothing to force them to buy. Now California, I hasten to add, is too big to fail. I mean you can predict dire things, they can run out of cash, but somebody will come to the rescue and the only party to come to the rescue if they don’t get their own house in order will be the federal government.

There will be a solution, but I think it’s way better if the solutions arrive early rather than late. I mean Benjamin Franklin said a lot of wise things but when he said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, I mean that is the guiding light at Berkshire and should be the guiding light for everybody with fiscal problems of any kind. California’s an enormously rich state. It’s not going to float off into the ocean or anything like that. It’s a terrific economy actually, it’s got an added business problem but all that’s solvable. But if it is not solved soon, it’s a few minutes before midnight on that and then it will get solved by somebody else for them and I just think that’s a terrible mistake.

You need leadership that has got the guts to come up with the kind of program that is required and has the ability to communicate it both to the people of California and in turn to the credit markets. The burden of proof has now shifted in the credit markets to “show me” on behalf of California. That burden of proof is, California will have to make sense, they won’t be able to do it with smoke and mirrors next year because they’ve got markets that will look very carefully at where the cash is going to come from and how it’s going to go out. You’ve got a lot of stuff out there that’s mandated, that leaves you less room to maneuver both for taxes and expenditure than you might have in many other states. They will have a situation where to some extent the general electorate has set rules for both income and expenditures that ties the hands of people and having set those rules, the people who set them really didn’t have a responsibility for making things. They just hit the bulldog for this or that. It’s an interesting problem; it will get solved.

The good news is, it’s like this country. Peter Lynch says when you buy stock, buy into a business that’s so good that even a dope can run it, because sooner or later one will. There’s a lot of merit to that. If you just buy businesses that your idiot nephew can run, you’re going to do all right. You don’t want a business that a genius has to run. That’s the worst kind of business in the world really. And the truth is, our country is so good that we can take a fair amount of mismanagement. We test that occasionally, but we come through too.

On that bullish note, it’s nine o’clock. Thank you.

Governor Leavitt: Thank you, Warren; I don’t think there’s anything we could say that would express adequately the appreciation people feel. Two things left, one is a pitch and the second is a picture. If you would like to have your picture taken as a memento tonight with Warren Buffet, he’s prepared to come stand, take some pictures with you if you would like. Now for the pitch: I want to make sure you understand what we are doing here in terms of the Oquirrh Institute. Most of you will know that the Oquirrh Institute is essentially a bunch of people who believe in entrepreneurship and apply the principles of entrepreneurship so you can solve some innovative public policy problems. The Oquirrh Club is what we are celebrating tonight—a group of people who come together twice a year and do what we are doing tonight. We’ll have a unique day of recreation, a chance to learn some things, and third we get to meet some great people—a wonderful network. Some of you have been invited as guests tonight to get acquainted with the Oquirrh Club. You can count on the fact that somebody will call you asking if you want to join; we hope that you do. We anticipate getting our numbers up to 50. We have been building up this year, with 34 thus far. When we get to 50 we are going to cap this program. It’s a great institution and I think you’ll see over the course of the next few years that Oquirrh Institute will probably become one of the country’s most prominent public policy organizations because of the unique model that we are using. Thank you all very much.

You should know that Dell Loy, through his generosity—his bounteous generosity—has helped get the momentum started for the Oquirrh Institute with a very generous 1 million dollar gift to get this started. A picture of Early Light. Most of you know the meaning of Oquirrh is early light. It’s a Goshute Indian word. The Oquirrh Mountains—the Indians saw the mountains and said they liked the way they looked when the sun hit. Dell Loy, this picture won’t do it. You know what’s inside my heart and inside the hearts of your friends. Thank you very, very much.

Dell Loy Hansen: I can speak for myself and almost everybody else in the room that I’ve met that the reason we’re here is quite simple. We all have one and the same answer—it’s Mike Leavitt. Now once we got here we all found a lot of very, very interesting things to get together with and go forward and do. But we all know the catalyst for this organization was Mike Leavitt—there’s no doubt about that in my mind. And so we have a token of gratitude to him. But there’s another thing we can do for him and I think it’s even more important than this token that we will give him. And that’s to remind ourselves that the best gift we can give to Mike Leavitt is to make the Oquirrh Institute prosper and grow and make it better than it is so that when he comes back there’s a bigger and better institute for him to come back to and to lead in the future. So with that, let me present to you: To Governor Michael O. Leavitt, founder of the Oquirrh Institute, shining early light on public policy.

Thank you all very much for your friendship. As Warren was talking tonight about loving what you do, I must tell you, I love what I do. I’ll hang this at the EPA but I’d be afraid somebody would come in and ask if that that was CO2. It’s a reflection. Thank you all very, very much for your friendship and what you are doing to make this work. This is going to be, I believe, an organization that will make great contributions to the world. Thanks.

Transcript of "An Evening with Warren Buffett"

October, 2003

Eagle Run Golf Resort

Omaha, Nebraska

Warren Buffett: Last year, as you may remember, was not a good year for Nebraska. It was their worst in about four years. It got so bad that Frank Solich, our coach, was addressing a group like this and he asked for our help and he said, “What we really need is a fullback. And the guy I have in mind would be about 6’4”, and weigh 130 lbs.” He said, “That might seem like kind of an odd requirement for a fullback, but it’s the only kind of guy who could get through the hole if the line opens up.”

So we found our fullback. We have a lot of student athletes at Nebraska and I asked one of them the other day, “What does that big N stand for on your helmet?” And he said, “Knowledge.” He was close.

I’m here to answer your questions. I’ll ask one of them myself. It’s “How did you get involved in the Schwarzenegger campaign?” The answer is, “I won a look-alike contest. Saddam Hussein has a double and Arnold felt he needed one too.”

The Governor mentioned something in his talk that provided me with a question I sometimes get asked by people: “How do I get into a marriage—younger people ask me—how do I make sure I get into a marriage that will last? What do I look for in a spouse?” It’s an important question. They say, should I look for humor, character, intelligence, looks? I tell them, “If you really want a marriage that will last, look for someone with low expectations.” And I’m glad the Governor’s taking that attitude to Washington with him.

Now let’s talk about what’s on your mind. Anything goes. We’re all off the record—although, actually, I see something going on back there (the video camera). I’ll try to be as candid as possible.

Mayor Riordan: Warren, we talk about the gap between the rich and the poor and for a variety of reasons, the number of middle class is dwindling in this country. The buying power of the middle class has been dwindling for the last 30 years. What is this going to lead to? What do you picture the country being like 10 years from now?

I would say that, absent a progressive income tax system, and an estate tax, that the nature of compound interest, and the nature of a more and more specialized economy, will lead to greater and greater differences between the very top and the bottom. If you go back a couple hundred years in this country when we had four million people, you could take people with an IQ of 90, and they could satisfy 80% of the jobs in the country—whether it was farming, or tradespeople or whatever. As the economy has become more specialized, more advanced, and all that, the rewards and the job profile of what pays well compared to other jobs and so on, just gets tilted more and more and more toward people who are wired in some way or have special talents that enable them to prosper in a huge way in a 10 trillion-dollar-plus economy and disparities will widen. And basically we have had a system in this country that, through the tax system in various ways, has sought to temper what a market system will produce in the way of distribution and wealth. You really have unchecked, as it was many years ago, unchecked, you will have families like mine, or whomever, people that bring a small edge over the rest of the populous. They will prosper at a rate that continuously outpaces the others.

And you can see it in entertainment. If you’re a Frank Sinatra or something now and you have some edge over the others—the ability to sing to 280 million people, or if you’re the heavyweight champion with the ability to be seen in the homes of 280 million people or whatever number—it’s worth far more relative to the general laborer pay than it was 50 or 75 years ago. All technology advances and all productivity advances and the pure market system work toward greater inequality of wealth and we have a system in this country where generally we have sought to temper that somewhat through a progressive income tax and through the estate tax in the last ten years or so—and particularly over the last five years—we’ve seen a reversal and I think it could have some very unfortunate consequences over time.

I was lucky to be born here at this time basically. I’m wired to be good at capital allocation. I get no credit for it—I came out of the womb that way. I’ve worked at it, but people work at all kinds of things in this country and all countries to work at the job they’re in. But I was wired in a way where in a huge capitalistic economy, just taking little bites off what’s available, I could amass enormous sums of money. If I’d been born two hundred years ago that would not have been available to me. If I was born in Bangladesh it would not be available to me.

Now people who think they do it all themselves, I pose to them the problem of let’s just assume they were in the womb as one of two identical twins—same DNA, same wiring, everything the same—and a genie came along and said one of you is going to be born in Bangladesh and one of you is going to be born in the United States. All the human qualities are the same. Which one will bid the higher percentage of the income they earn during their life to be the one born in the United States? The bidding would get very spirited. I mean, all these qualities of luck and pluck and all these things that are supposed to take us to the top—you know, like Horatio Alger—would not work as well in Bangladesh as here. This society delivers huge opportunities to people who happen to have the right wiring. And it delivers a pretty damn good result to people who could function here compared to the rest of the world and compared to a hundred years ago; but the disparity will widen absent the taxation system. That’s one of the things you need government for in my view.

Our market system is a wonderful system. You look at this country and it’s interesting. In 1790, we had just a little under four million people. Europe had 100 million people. China had 300 million people. So here’s this little country—and our IQs might be different from the Chinese people or the Europeans—and they have natural resources and we have natural resources, but somehow those four million people have gotten to where they have close to 35% of the GDP of the world, even though they only have 4 billion—4 _ percent of the world’s population. What has happened here? Here we’re in this race—it’s only been going on now for 210 years against 300 million people in someplace else that are just as smart as we are. But somehow our system has delivered this incredible bounty. I believe the two most important things in that and they’re far from perfect—but I think we have more equality of opportunity so that the right people get to the top. The right guy ends up being on the Olympic team of science, or business, or medicine or whatever because we have not had the artificial barriers to quality rising to the top in various areas.

And the second system is the market system and we have had an inducement for people to purchase what people want and that has all kinds of wonderful fallout, but it also results in an incredible inequality of wealth over time and absent the estate taxes—well, with just compound interest, you could take my grandsons and you’d have a significant percentage of wealth eventually. And you need something that tempers where the market system leads to but you don’t want to screw up the market system. You want to let them make it first. You want to keep the Andy Groves or whether it’s Michael Dell or whomever, you want to keep those people working, long after they’ve got all the things they need in life. You want that energy and that talent working, because it does work for the benefit of everybody, but then you need to have something that prevents huge concentrations of wealth.

QUESTION: Along the same lines, I heard a speaker from India who talked of why America’s thriving—because in India, you know your dad’s a chemical engineer and that’s what you’re gonna be—whereas Americans under Christianity and capitalism think we can take and should get whatever we want. My question is how would you solve the terrorism threat—when people hate us now because of our wealth and freedom?

It’s the ultimate problem. I felt that way after 1945 because essentially you always have people who are psychotic or megalomaniacs or just plain evil or religious fanatics or whatever it may be. There is a certain percentage of people who for one reason or another are sociopaths and thousands of years ago their ability to afflict harm on their fellow man was the ability to throw a rock at somebody and it gradually went to bows and arrows and guns and a few things. But up until 1945 the ability of misdirected people—which will be more or less proportionate to the population over time (maybe you could make an argument that prosperity may reduce it a little bit) but there’s just a lot of screwy people. I mean, I’ve been to the mental institutions in Nebraska and my father-in-law taught psychology and I used to go down with him—I mean, there are just people who are not very well fit for society and until 1945 their ability to afflict harm on their fellow man had progressed, but it had progressed at a tolerable level. At the time of Hiroshima and from that point forward, there’s been this exponential increase in the ability of deranged people who one way or the other—perhaps leading governments, perhaps acting some other way—to inflict incredible harm on their fellow man.

It takes four things. It takes intent and there will always be a certain amount of intent in the world. There will be people that are envious; there will be people that are crazy and so on.

It takes intent. It takes knowledge. It takes materials. It takes deliverability. The knowledge has spread. We had a monopoly on nuclear knowledge in 1945 and thank God we had it because if Hitler hadn’t been so anti-Semitic, basically, he might well have had it before we had it. But we got the knowledge first. Most of you aren’t old enough to remember, but Hitler was lobbing those B-1s and B-2s over into London, but the warheads were nothing. But if he’d gotten them first, it would be a different world, or maybe no world.

So the knowledge since ’45, when we had the monopoly on this incredible knowledge, has spread. You have Pakistan, you have India, you have individual groups. Materials are tougher in the nuclear arena. Now if you get into bio the materials get easier but we still have the same levels of damage. But you get suicide bombers and things like that and the materials are peanuts in terms of cost and the knowledge is there. It is a problem that we do not have a perfect answer for and all we can try to do is reduce the probabilities of somebody successfully doing something on a large scale. It will happen. It will happen with nuclear. In my view it will happen with bio. Probably a little more likely to happen with bio in the next, say, ten years than with nuclear but the truth is there are a lot of people that have the ability to do things. I’m in the insurance business, and anything that can happen will happen.

If you take the last 300 years in America, where do you think the largest earthquake was in the continental United States? It was in New Madrid, Missouri. 8.6. The Mississippi River ran backwards. Church bells rang in Boston. Another big one was in Columbia, South Carolina, and everybody’s forgotten about that. It killed 70 or 80 people, 6. something. Things happen over time. You just can’t keep drawing balls out of a barrel with ten thousand white balls and four black balls, we’ll say, without eventually drawing a black ball. We almost drew one during the Cuban missile crisis. It was touch and go. We sent the second message, then the contact with the guy from ABC. But there was a lot of luck involved. I know people who were there at the table. And they didn’t know if their kids were going to be alive some weeks later. But we got through it. And basically, we’ve been very lucky, but we’ve also done the right things over that time. It doesn’t work forever. The bio thing, I mean, it’s scary. Anthrax isn’t as easy to deliver. The deliverability of Anthrax is a problem. You can take the amounts in those few envelopes and it would kill a hundred thousand people but it’s a problem to disperse. The progress of weaponry over the years (if you want to call it progress) has been dramatic.

When I formed my foundation in the late ‘60s, I said that the number one problem was the nuclear threat and I just don’t know how to attack it with money very well. I support something called the nuclear threat initiative.

The great problems of society are the ones money won’t solve. Probably true in your families too. The problems you have where money doesn’t help—those are the real problems. The problems that money can help, this country can one way or another solve. And the ultimate one is the one you mentioned there. There are people in the world that want to do us great harm. We’re more the target than anybody else. Some of them will have the knowledge, fewer will have the materials; they won’t have the deliverability.

But North Korea—there’s a small probability in the next year that something happens with North Korea. I don’t know whether it’s .01 or .03 or .005, but it is a probability. There’s some probability of it. And there’s a probability of all kinds of other things. People would have thought it was science fiction if you’d have written about what would happen at the World Trade Center a few years ago. That 20-odd people could carry it off with box cutters and so on. It’s the problem of mankind. Our job is to reduce the probability in every way we can. The number one way is to try and do whatever you can to deter the further spread of nuclear weapons. Like India and Pakistan each have that ability and they have the hatred that’s existed over the years and the sort of incidents that developed by accident.

President Clinton was here last Saturday at my daughter’s house and we had lunch and we were talking about India and Pakistan. He worked on a solution I think it was right on the eve of the State of the Union message a few years back. And he didn’t know whether something was going to break out or not. The consequences are just huge. It’s the number one problem of mankind. I don’t have any great answers, but I think that the Commander in Chief—it’s his number one job. Whatever it may take in terms of our borders, in terms of solving the problems of stockpiles around the country, cooperating with the Russians, get rid of a lot of the material like that. It will be the problem of your lifetime and your children’s and your grandchildren’s.

With all the storm of regulation in the last couple of years on the subject of corporate governance, could you say something about your views of the essentials of good corporate governance?

Well, I’ve got a somewhat different view. I’ve been on 19 public boards and corporate business boards over 40+ years, public companies, not counting anything Berkshire controls. And I’ve seen a lot of interaction of boards. And the problem has been overwhelmingly that boards, despite the fact that they exist in a business environment, tend to be social organizations. I think it’s very difficult for these people on the board—(I was put on the board of Coca-Cola in 1988)—to go in there and start questioning Roberto Goizueta in terms of his compensation. And incidentally we didn’t even know as board members what the compensation was. I mean you read the proxy statement unless you were on the comp committee. And they never put me on the comp committee. And I’ve been on all kinds of committees. They’ll put me on the greetings committee, the gardening committee—anything really, the dance committee. They don’t put me on the comp committee—I wonder why?

But it’s a social organization to a great degree. And generally speaking, the only thing, absent a very large shareholder who’s unhappy with something going on—the only things that really cause change is when people on the board get embarrassed. Because you get a bunch of big shots on the board. I call it “elephant-bumping” when you go to board meetings. Everybody looks around and you see all these elephants, and you think “I must be an elephant too.” It’s very reassuring. You don’t want to sit there and belch in a board meeting because it just isn’t done, like questioning comps and questioning acquisitions, and other things worse than belching (we won’t get into what that is). But it’s a social operation and the question is—how do you break out of something like that? And it’s not easy. The hardest problem is dealing with mediocrity.